After many years in which the media only highlighted the continuous rise in house prices without addressing the root causes (which we’ve discussed several times on this blog), a recent article from Dutchnews finally touches on them: “Dutch homes are unaffordable because that’s what officials want”. It's a bold statement, but is it wrong?!

1) The Average Property Price

Let’s begin with the price itself. As of June 2025, according to the article, the average house price in the Netherlands exceeds €472,000!

Since this is an average, it means a significant number of homes are priced in the €200,000–€300,000 range, while many others fall in the €600,000–€700,000+ bracket.

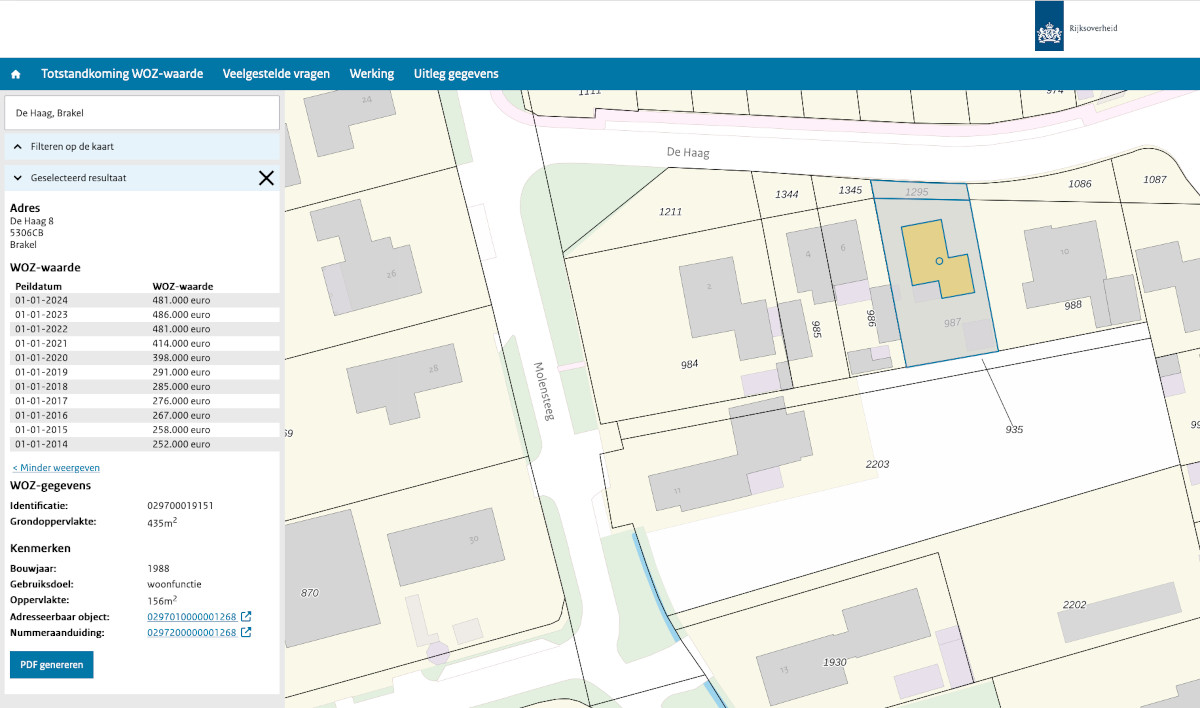

Over the past decade, it’s safe to say that property prices across the country have nearly doubled. If you’re curious about individual property values, you can easily check them via the official government portal: wozwaardeloket.nl .

Note: WOZ-waarde stands for “Waarde Onroerende Zaken” (Value of Immovable Property) — the Dutch government’s annual valuation used for tax purposes.

2) The Main Driver – More Borrowing Power

Indeed, the Netherlands is heavily overleveraged, and banks have made borrowing extremely easy — arguably too easy. This is partly because banks know they’re likely to be bailed out by the government (and ultimately, the taxpayers) if things go wrong.

The reason Dutch houses are so expensive is because people (are allowed to) borrow so much money. The Netherlands has Europe’s highest borrowing compared with GDP – almost 100%. This doesn’t just mean money which could be used to fund economic activity and scale-ups goes into dead bricks.

In 2023, the former housing minister Hugo de Jonge* removed one of the last brakes on lending. Previously, you could only account for part of a second partner’s salary to get a mortgage. The Nibud household budget institute says before 2012, a second income was not counted at all

* does this name ring a bell to you? COVID era, look for details.

Adding a second income (e.g., a partner’s salary) into the mortgage application dramatically increases borrowing power. Try it yourself at De Hypotheker’s calculator.

Let’s take a hypothetical couple:

Age: 30

Gross annual salaries: €45,000 and €35,000

Result:

Maximum mortgage: €372,980

Monthly gross cost: around €1,700

Term: 20 years, with fixed interest at 3.73%

In many other European countries, such borrowing levels would be unthinkable without a significant down payment — yet in the Netherlands, it’s normalized (and suicidal from the economic point of view).

In the Netherlands, top earners can borrow 5.5 times their salary and up to 100% of a home’s value (or even 110% for energy-efficient renovations).

3) Interest Rate Gimmicks

Of course, this massive borrowing generates considerable interest over time. Various schemes are in place to soften the blow, such as fixed interest rates for up to 30 years. But the most significant is the mortgage interest deduction (Hypotheekrenteaftrek).

For 2025, the government will cover up to 37% of your interest payments — which sounds generous, but the money comes from general taxation. In effect, all taxpayers are subsidizing homeowners.

This creates a distorted market in which monthly mortgage payments are often lower than rent, pushing more people into buying — further inflating demand.

The hypotheekrenteaftrek mortgage deduction, which gives people with mortgages lower tax than renters, was scrapped by most countries decades ago because it skews the market, increases debt and reduces rental supply.

In fact, everyone in the Netherlands could pay 1.5% less in income tax if that €8.9 billion were not used each year to subsidise home ownership.

4) The Real Culprit

Contrary to popular belief, the problem isn’t mainly foreign investors buying up property. It’s the government’s interference in the housing market, which — under the guise of making homeownership “more accessible” — is in fact fueling unsustainable price growth.

If market forces were allowed to act freely, without subsidies and artificial incentives, prices would reflect real supply and demand. But that’s not in the government’s interest. Why?

5) Why the Government Prefers High Prices

The Dutch government has several incentives to keep WOZ values high:

A. Higher Tax Revenues

Many taxes are based directly on WOZ value, including: OZB (Property tax), Waterschapsbelasting (Water board tax), Eigenwoningforfait (Imputed income for homeownership in income tax), Gift and Inheritance Tax, Sewer & Waste Charges (Afvalstoffenheffing & Rioolheffing)

The higher the WOZ value, the more tax the government collects.

B. Illusion of Wealth

Rising home prices create a false sense of prosperity. Homeowners feel richer, even if their net wealth is tied up in long-term debt. This illusion fuels consumer spending — on renovations, cars, holidays — funded by re-mortgaging and additional debt.

Yet this perceived wealth is just that: perception. It's more debt, not more assets.

C. Retirement Hopes

Many Dutch citizens hope to “cash out” when they retire, since: the state pension is modest, occupational pensions vary and private savings are often insufficient. A housing crash would threaten this plan — leaving many pensioners in a precarious position.

D. Systemic Risk

If house prices fall significantly, banks will be affected. Borrowers would be stuck paying €500,000 mortgages on homes worth €300,000 — a recipe for economic instability.

Banks may panic and demand additional collateral, triggering forced sales and even defaults. The debt spiral would become a national crisis.

6) The Bubble Spiral

The loop continues:

Borrow more ➝ Prices rise ➝ Borrow even more ➝ Repeat

But the system is cracking: home prices are now so high that entire demographics are priced out, especially young single workers. The dream of homeownership is slipping away for anyone earning near the minimum wage. At this rate, half the Dutch population will soon be “millionaires” on paper — thanks solely to inflated house values.

But what goes up eventually comes down. And when it does, the consequences will be painful.